Mia Tsai, Author

|

(If you missed the first Flights of Foundry roundup post on critique, have no fear! Click here.)

I have to admit fault: while I did indeed get busy between the last blog post and this one (copyedits and proofreads on books not mine, reading manuscripts, JAMDAM, revision turned in, book 2 pitch and synopsis turned in, personal life stuff), I was reluctant to write it not because I didn’t know what to say, but because I didn’t know what order to say things in. I’m a teacher—a pedagogue, no less—and information flow is a critical issue for me. And so I hesitated for over a month on tackling decolonization, even in the sort-of narrow scope in which we talked about it during the Decolonizing our Narrative Traditions panel at Flights of Foundry. I figured eventually that I’d have to bite the bullet and go for it because some writing is better than no writing. It’s funny to me how I typically don’t get writer’s block when I’m working on a novel, but I’ll get stuffed up for blog posts. So here I am, unsticking the pipes (does this mean I should write a post about writer’s block?). I’d been highly anticipating the decolonization panel since I found out I’d be on it, and it’s no secret why. I’m passionate about how colonialist and imperialist ideas filter into speculative fiction specifically, and I’m always excited to chat about this topic, especially with a moderator and panelists I like and admire. Our moderator was the wonderful Vida Cruz (vidacruz.org; here’s her Ways to Decolonize Your Fiction Writing presentation from FoF 2021), and I was joined by panelists Zhui Ning Chang (zhuiningchang.com), Fatima Taqvi (fatimataqvi.com), and Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki (odekpeki.com; congratulations go to Oghenechovwe again for his Nebula win for “O2 Arena”). Prior to the panel, Vida sent out a list of questions for us to peruse and possibly to discuss in the prep stage. I’ll admit that I prepped more for this panel than my other panels. I rarely write a full page of notes, but I went top to bottom in my notebook for this. And that was before I started addressing the questions Vida had sent. A look back at the email chain revealed our discussion of what exactly decolonizing our narrative traditions meant. Did it mean consciously removing colonialist and imperialist thinking? Did it mean exploring non-three-act structures and educating Westerners on what they were, their history, and what to expect? Did it mean creating fiction set in post-colonial worlds? (Now that I’m thinking about it, it’s no wonder I had a hard time finding a starting point for this blog post.) We tried to address all the above questions during the panel, beginning with non-Western storytelling structures. By now, many people have heard of the East Asian four-act, which in Japanese is called kishoutenketsu (spelled here with an ou because I can’t for the life of me find the o with a macron) and in Chinese is called 起承轉結 (qǐ chéng zhuǎn jié, start/rise continue turn conclude), and Zhui Ning talked a bit about it. It’s the format that Henry Lien has lectured on (here’s a link to his blog post for SFWA: https://www.sfwa.org/2021/01/05/diversity-plus-diverse-story-forms-and-themes-not-just-diverse-faces/). For me personally, a structure that’s remained with me is less of a structure and more of a style, which is the episodic format that many Chinese epics use. For example, in the wuxia classic Legend of the Condor Heroes, each section has its own rising and falling action, which when compiled with the many other sections reveals an overall plot arc. Fatima talked about a Persian and Urdu epic form called dastan/dastaan, which I won’t elaborate on in this post because I’m not familiar with it! But the heart of it involves a Big Hero and a joker/jester sidekick character. And Oghenechovwe talked about how, growing up in Nigeria, he had access to Western science fiction and fantasy—demonstrating the reach of Western literary norms. What I found quite interesting about the panel was when Oghenechovwe began talking about what decolonization in speculative fiction meant to him: a tight focus on local events, for example, and centering character. I’d go more into detail, but it’s been a couple of months and the memory is fuzzy. But then he dovetailed into climate fiction as decolonial, which, I admit, kind of blew my mind because of how correct he is. Cli-fi often involves a breakdown of social norms, a reshuffling of political and economic power, usually with movement to the extreme ends of the spectrum, and deals with local impacts of a changing climate or climate disaster. Climate fiction is growing increasingly popular these days, and it’s no surprise to me why that is: traditional publishing is overwhelmingly Western and white, and as climate change begins to threaten Western cities, more people are turning to cli-fi as a means of processing what might happen to them in the future. It’s inherently human not to care about an issue until it personally affects you, but it’s also indicative of how strongly the West centers itself when it comes to ongoing global crises. Perish the thought of New York City or Miami being lost to hurricanes or for Los Angeles to be lost to wildfires. Meanwhile, for many non-Western people, especially those in island nations, living on the coastlands of the Global South, or in zones where extreme weather already exists and is being exacerbated by temperature rises, climate fiction isn’t fiction but reality. That brings me to what I wanted to address most on the panel but didn’t get to because of time constraints. Again, I’m a teacher at heart, and I always want to know concretely what something is and what to do about it. For some in attendance, the definition of colonialism remained murky, and thus the concept of decolonization couldn’t be grasped tightly because of the lack of definition. Our dictionary (Merriam-Webster, the industry standard) says thus: co·lo·nial·ism, noun inflected form(s): plural -s 1: the quality or state of being colonial 2: a custom, idiom, idea, notion, or style characteristic of a colony: provincialism 3: the aggregate of various economic, political, and social policies by which an imperial power maintains or extends its control over other areas or peoples: practice of or belief in acquiring and retaining colonies It’s somewhat informative but doesn’t grant a larger picture. For myself, in my notes, I jotted down what I think are hallmarks of colonialism in SFF:

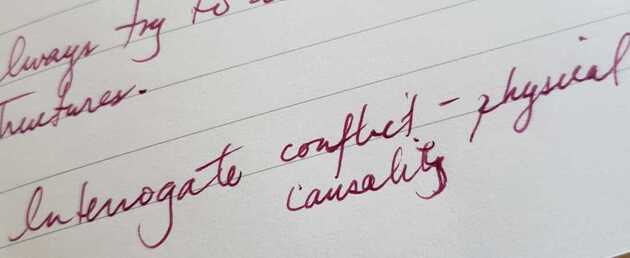

These are big ideas to take in. After all, so much of science fiction and fantasy is about imagining another world, or about the movement of nations against each other on grand scales, or about how heroes must rise to fight against invading kingdoms. A lot of classic horror leans on the fear of becoming or encountering an Other or embracing a breakdown of societal structure. When we think about decolonizing SFFH, it might feel like an insurmountable task to toss these underpinnings. But it’s not impossible. I’d encourage authors who want to interrogate the colonial assumptions of SFFH to start with one or two ideas. What happens, for example, if we do away with exploration stories or reframed exploration as a violent act? What role does direct conflict play, and can story events unfold without causality? What if we asked whether religion is necessary and whether it needs to have moral code or guide to “good” and “bad”? Is it necessary to spread religion? And from there, the next step might be asking what sovereignty means in a secondary world, or what importance borders have. What role does royalty play, and does royalty have a place in a secondary world? If there are classes based on wealth, where does the wealth come from and who does the labor to produce the wealth? Is any of that truly necessary? And if it is, what would you as the author like to say about those structures? Try narrowing the scope to a village or town or city-state. Examine whether the political ideas championed by the West in the twentieth century are needed in this world. Western democracy, for example, isn’t always the best form of government and neither is monarchy. Delve into older structural forms that already exist in the West but have been erased by Hollywood’s cultural hegemony (or the English, or the French, or the Portuguese, or the Spanish, or whoever’s been conquering other people at any given time in Western European history). Imperialism touches us all, and Europeans are no exception. Be inspired by non-book structures, like two-act plays or Shakespeare’s five-acts. Look to folk tales, song cycles, or oral histories. I’m deliberately not speaking of non-Western forms here because I want marginalized authors to be centered within that space and to have the opportunity to tell their tales before getting Columbused by publishing. And so it comes full circle back to what I as a Taiwanese American author might choose to write about or not write about. Taiwan is, in a word, complicated. I am the product of colonists who have had a long history of being colonized, and I was born in and currently live in an imperialist nation built on genocide and chattel slavery. Over the centuries, Taiwan has been colonized by the Chinese, the Portuguese, the Japanese, and the Chinese again, and only in the last several decades have the Taiwanese been able to self-determine and come to grips with their multiply-colonized history. Still, Chinese imperialism is both the mailed fist and the velvet glove. It’s an open violence and a subtle violence. Mandarin was my first language, not Taiwanese Hokkien, and that's because of the martial law imposed on Taiwan that banned Taiwanese from being spoken. When I consider my background, it can sometimes be incredibly depressing to see how deeply colonialism has impacted me and how I may unwittingly write that into my work, which necessitates a lot of thinking and turning story concepts over and over, sometimes for years. But that’s how it goes, right? Decolonization is a moving target. All I can do is try not to mimic without thought and hope that others out there can begin to see how colonialism and imperialism is woven into our society—because once we can see clearly, a new horizon will open to us. And I look forward to reading fresh, exciting literature as a result.

1 Comment

|

AuthorMia is a musician, teacher, writer, editor, and occasional photographer whose formal education is in music, psychology, and pedagogy. She enjoys reading a lot, thinking while on long drives, finding songs for each moment, and snoozing with her cat. Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed