Mia Tsai, Author

|

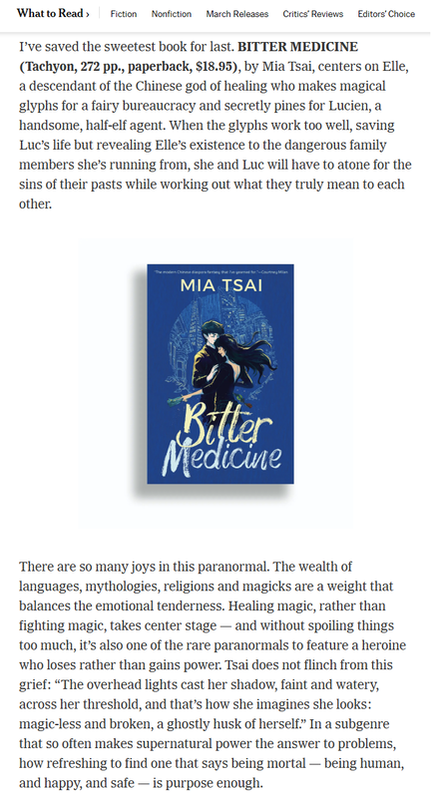

I've neglected this blog pretty hard in the last year; I really thought I'd update it more (and then I got the newsletter instead). But I just wanted to update this really quick with the lovely review Bitter Medicine got from the New York Times Review of Books!

0 Comments

It's here, and it's beautiful! Thank you to my editor, Jaymee Goh, for all her work, and my artist, Jialing Pan, for delivering a gorgeous cover. Check out more of Jialing's work here: https://jialingpan.com/ As a descendant of the Chinese god of medicine, ignored middle child Elle was destined to be a doctor. Instead, she's underemployed as a mediocre magical calligrapher at the fairy temp agency, paranoid that her murderous younger brother will find her and their elder brother.

Using her full abilities will expose Elle's location. Nevertheless, she challenges herself by covertly outfitting Luc, her client and crush, with high-powered glyphs. Half-elf Luc, the agency's top security expert, has his own secret: he's responsible for a curse laid on two children from an old assignment. To heal them, he'll need to perform his job duties with unrelenting excellence and earn time off from his tyrannical boss. When Elle saves Luc's life on a mission, he brings her a gift and a request for stronger magic to ensure success on the next job - except the next job is hunting down Elle's younger brother. As Luc and Elle collaborate, their chemistry blooms. Happiness, for once, is an option for them both. But Elle is loyal to her family, and Luc is bound by his true name. To win freedom from duty, they must make unexpected sacrifices. Preorders are the best way to support authors! It gives the publisher an early idea of how much interest there is in the book. If you're so inclined, the preorder link is here: tachyonpublications.com/product/bitter-medicine/ (If you missed the first Flights of Foundry roundup post on critique, have no fear! Click here.)

I have to admit fault: while I did indeed get busy between the last blog post and this one (copyedits and proofreads on books not mine, reading manuscripts, JAMDAM, revision turned in, book 2 pitch and synopsis turned in, personal life stuff), I was reluctant to write it not because I didn’t know what to say, but because I didn’t know what order to say things in. I’m a teacher—a pedagogue, no less—and information flow is a critical issue for me. And so I hesitated for over a month on tackling decolonization, even in the sort-of narrow scope in which we talked about it during the Decolonizing our Narrative Traditions panel at Flights of Foundry. I figured eventually that I’d have to bite the bullet and go for it because some writing is better than no writing. It’s funny to me how I typically don’t get writer’s block when I’m working on a novel, but I’ll get stuffed up for blog posts. So here I am, unsticking the pipes (does this mean I should write a post about writer’s block?). I’d been highly anticipating the decolonization panel since I found out I’d be on it, and it’s no secret why. I’m passionate about how colonialist and imperialist ideas filter into speculative fiction specifically, and I’m always excited to chat about this topic, especially with a moderator and panelists I like and admire. Our moderator was the wonderful Vida Cruz (vidacruz.org; here’s her Ways to Decolonize Your Fiction Writing presentation from FoF 2021), and I was joined by panelists Zhui Ning Chang (zhuiningchang.com), Fatima Taqvi (fatimataqvi.com), and Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki (odekpeki.com; congratulations go to Oghenechovwe again for his Nebula win for “O2 Arena”). Prior to the panel, Vida sent out a list of questions for us to peruse and possibly to discuss in the prep stage. I’ll admit that I prepped more for this panel than my other panels. I rarely write a full page of notes, but I went top to bottom in my notebook for this. And that was before I started addressing the questions Vida had sent. A look back at the email chain revealed our discussion of what exactly decolonizing our narrative traditions meant. Did it mean consciously removing colonialist and imperialist thinking? Did it mean exploring non-three-act structures and educating Westerners on what they were, their history, and what to expect? Did it mean creating fiction set in post-colonial worlds? (Now that I’m thinking about it, it’s no wonder I had a hard time finding a starting point for this blog post.) We tried to address all the above questions during the panel, beginning with non-Western storytelling structures. By now, many people have heard of the East Asian four-act, which in Japanese is called kishoutenketsu (spelled here with an ou because I can’t for the life of me find the o with a macron) and in Chinese is called 起承轉結 (qǐ chéng zhuǎn jié, start/rise continue turn conclude), and Zhui Ning talked a bit about it. It’s the format that Henry Lien has lectured on (here’s a link to his blog post for SFWA: https://www.sfwa.org/2021/01/05/diversity-plus-diverse-story-forms-and-themes-not-just-diverse-faces/). For me personally, a structure that’s remained with me is less of a structure and more of a style, which is the episodic format that many Chinese epics use. For example, in the wuxia classic Legend of the Condor Heroes, each section has its own rising and falling action, which when compiled with the many other sections reveals an overall plot arc. Fatima talked about a Persian and Urdu epic form called dastan/dastaan, which I won’t elaborate on in this post because I’m not familiar with it! But the heart of it involves a Big Hero and a joker/jester sidekick character. And Oghenechovwe talked about how, growing up in Nigeria, he had access to Western science fiction and fantasy—demonstrating the reach of Western literary norms. What I found quite interesting about the panel was when Oghenechovwe began talking about what decolonization in speculative fiction meant to him: a tight focus on local events, for example, and centering character. I’d go more into detail, but it’s been a couple of months and the memory is fuzzy. But then he dovetailed into climate fiction as decolonial, which, I admit, kind of blew my mind because of how correct he is. Cli-fi often involves a breakdown of social norms, a reshuffling of political and economic power, usually with movement to the extreme ends of the spectrum, and deals with local impacts of a changing climate or climate disaster. Climate fiction is growing increasingly popular these days, and it’s no surprise to me why that is: traditional publishing is overwhelmingly Western and white, and as climate change begins to threaten Western cities, more people are turning to cli-fi as a means of processing what might happen to them in the future. It’s inherently human not to care about an issue until it personally affects you, but it’s also indicative of how strongly the West centers itself when it comes to ongoing global crises. Perish the thought of New York City or Miami being lost to hurricanes or for Los Angeles to be lost to wildfires. Meanwhile, for many non-Western people, especially those in island nations, living on the coastlands of the Global South, or in zones where extreme weather already exists and is being exacerbated by temperature rises, climate fiction isn’t fiction but reality. That brings me to what I wanted to address most on the panel but didn’t get to because of time constraints. Again, I’m a teacher at heart, and I always want to know concretely what something is and what to do about it. For some in attendance, the definition of colonialism remained murky, and thus the concept of decolonization couldn’t be grasped tightly because of the lack of definition. Our dictionary (Merriam-Webster, the industry standard) says thus: co·lo·nial·ism, noun inflected form(s): plural -s 1: the quality or state of being colonial 2: a custom, idiom, idea, notion, or style characteristic of a colony: provincialism 3: the aggregate of various economic, political, and social policies by which an imperial power maintains or extends its control over other areas or peoples: practice of or belief in acquiring and retaining colonies It’s somewhat informative but doesn’t grant a larger picture. For myself, in my notes, I jotted down what I think are hallmarks of colonialism in SFF:

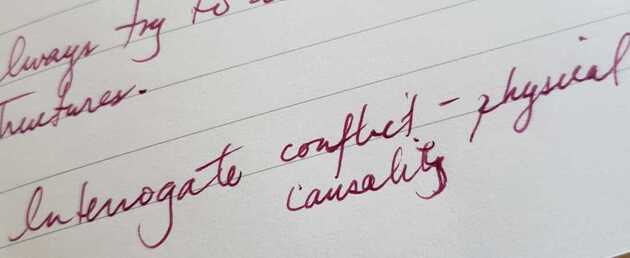

These are big ideas to take in. After all, so much of science fiction and fantasy is about imagining another world, or about the movement of nations against each other on grand scales, or about how heroes must rise to fight against invading kingdoms. A lot of classic horror leans on the fear of becoming or encountering an Other or embracing a breakdown of societal structure. When we think about decolonizing SFFH, it might feel like an insurmountable task to toss these underpinnings. But it’s not impossible. I’d encourage authors who want to interrogate the colonial assumptions of SFFH to start with one or two ideas. What happens, for example, if we do away with exploration stories or reframed exploration as a violent act? What role does direct conflict play, and can story events unfold without causality? What if we asked whether religion is necessary and whether it needs to have moral code or guide to “good” and “bad”? Is it necessary to spread religion? And from there, the next step might be asking what sovereignty means in a secondary world, or what importance borders have. What role does royalty play, and does royalty have a place in a secondary world? If there are classes based on wealth, where does the wealth come from and who does the labor to produce the wealth? Is any of that truly necessary? And if it is, what would you as the author like to say about those structures? Try narrowing the scope to a village or town or city-state. Examine whether the political ideas championed by the West in the twentieth century are needed in this world. Western democracy, for example, isn’t always the best form of government and neither is monarchy. Delve into older structural forms that already exist in the West but have been erased by Hollywood’s cultural hegemony (or the English, or the French, or the Portuguese, or the Spanish, or whoever’s been conquering other people at any given time in Western European history). Imperialism touches us all, and Europeans are no exception. Be inspired by non-book structures, like two-act plays or Shakespeare’s five-acts. Look to folk tales, song cycles, or oral histories. I’m deliberately not speaking of non-Western forms here because I want marginalized authors to be centered within that space and to have the opportunity to tell their tales before getting Columbused by publishing. And so it comes full circle back to what I as a Taiwanese American author might choose to write about or not write about. Taiwan is, in a word, complicated. I am the product of colonists who have had a long history of being colonized, and I was born in and currently live in an imperialist nation built on genocide and chattel slavery. Over the centuries, Taiwan has been colonized by the Chinese, the Portuguese, the Japanese, and the Chinese again, and only in the last several decades have the Taiwanese been able to self-determine and come to grips with their multiply-colonized history. Still, Chinese imperialism is both the mailed fist and the velvet glove. It’s an open violence and a subtle violence. Mandarin was my first language, not Taiwanese Hokkien, and that's because of the martial law imposed on Taiwan that banned Taiwanese from being spoken. When I consider my background, it can sometimes be incredibly depressing to see how deeply colonialism has impacted me and how I may unwittingly write that into my work, which necessitates a lot of thinking and turning story concepts over and over, sometimes for years. But that’s how it goes, right? Decolonization is a moving target. All I can do is try not to mimic without thought and hope that others out there can begin to see how colonialism and imperialism is woven into our society—because once we can see clearly, a new horizon will open to us. And I look forward to reading fresh, exciting literature as a result. A few days ago, I posted a picture on my Instagram, as well as a story, about my latest KitKat acquisition, the limited edition mini whole wheat biscuit (it tastes kind of like Teddy Grahams). I mentioned in passing that I have a whole spreadsheet of KitKat flavors and rankings thanks to my husband, and that I could probably blog about it. Turns out a number of people want to know about KitKat flavors!

So here's the blog post on the Japanese KitKats I have tried. I'm not going to beat around the bush. Here are my top five currently:

Here's the list of all the other KitKat flavors we have tried!

KitKats from Japan aren't cheap by any means. I've built this list over several years at the Buford Farmers Market, which I'm lucky enough to access fairly easily, but my budget gets blown to hell if I decide to buy a bunch of bags. I wish we could have local KitKat tastings, honestly! Where might you find these? I'd check your local HMart if you have one. Lots of online stores will sell these as well, most notably places like Bokksu. And if there are flavors you love (or hate), please feel free to leave a comment and let me know! Some quick wrap-up stuff: the submissions period for JAMDAM is currently going! Subs close on April 30, 2023. Click the link above for full details. I'm looking forward to reading your submission packets! And the next blog post will be about the decolonization panel at Flights of Foundry, I promise. Last weekend, I participated in my first Flights of Foundry, a free online convention for speculative fiction run by Dream Foundry. I had a good time and a pleasant experience, especially as someone who had four (4!!!) panels to speak on, as well as a chill-and-chat. Three of the panels were editing-related, and the fourth panel was on decolonization of (Western) narrative traditions.

The decolonization panel is going to need its own post and, quite possibly, a series of posts. I have strong feelings regarding colonization and how that's shaped Western science fiction and fantasy and our view of the Other because Western colonization has directly impacted how women of color are viewed and treated in Western society today. You can draw a straight line, basically, from things like the French invasion of Vietnam and Polynesia to violence committed against Asian and Pacific Islander women anno Domini nostri Jesu Christi 2022. That's getting a bit dark for this particular post, so I'm going to put a pin in that (this is now a phrase I lean on a whole lot? Apologies). This first post is about my panel, "Fiction Critiques: What to Take and Leave Behind." I got to sit on this panel with my lovely moderator, George Jreije (author of Shad Hadid and the Alchemists of Alexandria), and co-panelists Nino Cipri and Monica Louzon. And we had a great time thanks to George's editorial experience and relaxed, conversational moderation style. I did some prep prior to the panel, and I figured it'd be useful for newer writers or newer critics (sounds really judgy, yikes) to share that here. One of the most common questions I see is, "How do I give critique?" This is a broad question, so I ended up breaking it down into two categories: action feedback and vibes feedback. But before I address what those mean, I need to lay some foundational work. The best critique experience you'll have as either a writer or a critic/reader is to be specific in your parameters about what you want. That specificity will inform the type of critique you receive. So often, writers will ask for feedback from a reader and receive crit that's too harsh and too specific, or too nebulous or too general. Before you send out something to be read, think about what your goals are. I promise that you do have goals more specific than, "Is this good?" So: the types of critique. A lot of people talk about useful critique and not-useful critique, which makes sense to a writer because not all critique can be acted upon, whether it's because it's the wrong critique for you ("I don't get the Asian part") or critique that's incapable of engendering action ("I couldn't stay interested"). However, I'd like to reframe utility itself. Instead of calling crit useful or not, let's look at it as action-based critique and vibes/emotional/mood-based critique. Action-based critique, or action feedback, is specific and nonjudgmental. It is feedback that points to concrete aspects of your story and may indicate a solution. For example, "Too many events feel crowded into the middle or end and not the front" is actionable pacing critique. "I thought the inciting incident happened in chapter x on page n, and that occurred too far in for me" is also actionable because you can compare what your reader thought to what you intended and retune your story if there's a mismatch. Vibes-based critique, or vibes feedback, is vague and based on the reader experience. You can call vibes mood or emotion or feeling or gut. Vibes feedback is the reaction video of feedback. Reaction videos never give advice--and why would they? It's not like the creator of the video is able to fix anything now that the video is out. "The pacing felt off" is vibes feedback, as is "I couldn't connect to this character." This particular type of feedback has no immediate solution and may result in the writer going, "What does that mean? How do I fix this?" This doesn't mean vibes feedback isn't useful, though. It's data. Collect enough of it, and a pattern may emerge that you can then address in revision. To get a good crit experience, arrive at the table already knowing what you want. Do you want a gut check/up-down vote? That's vibes feedback or data collection feedback and puts the least amount of burden on your reader. This is not a bad way to test out potential readers, actually. Swap chapters, read for vibes, give your opinion (notice I did not say assessment). If you want something specific and actionable, ask for it. Do you feel your pacing/characterization/worldbuilding is off? Ask your reader to look at those things. If there's other feedback, that's a bonus! The opening moments of the panel were devoted to types of critique, and I rattled off several that got the audience asking questions. Essentially, as a writer, you can ask for a positivity pass, a gut check or first impression, or a detailed look at certain aspects of your story. These are and/or situations, but again, to alleviate reader burden, it's best to start with just one. A positivity pass is a read with positive feedback only. Gut checks ask the question, "Would you read on? Have I hooked you?" And the detailed look falls into the realm of the critique partner, the person who takes a magnifying glass to your story and zeroes in on its weaknesses. Ah, the critique partner. This term can be interchangeable with the beta reader or exist along the beta reader-critique partner continuum. Personally, I divide my readers into alpha readers, beta readers, and critique partners. My husband is my alpha reader, the person who sees whatever it was I just vomited and gives some general opinion-based feedback. He operates in the Mr. Le Guin sphere where he reads my thing and says, "That's good, honey," and that's all I want or expect from him. My writing friends are potential beta readers who read a chapter or two or half the book or the whole book and cheer me on or yell at me as needed. And my critique partner, of which I only have one currently, is my microscope user who watches my progress from chiseling the rock out of the mountain, to hauling it back to the studio, to staring at it to find what I'm going to sculpt, to smashing my thumb multiple times as I am tapping away. She gives me detailed breakdowns of chapters, an overarching look at characters, pace, and plot, and points out discrepancies in timeline of events and language usage. One warning, though, to close out this post, which is based on personal experience because we've all needed to start from somewhere (it's me, I was the asshole, and now I'm a copyeditor, so at least the nitpickiness was put to good use). Do not, unless the writer asks you to, "fix" grammar in someone's manuscript. Simply do not do it. It's overwhelming, first of all, and it's surface-level reading. Don't let the dressing of the writing distract you from the substance of the writing. Gently query the places where you are confused. But for the most part, you should be able to understand the intent and meaning of the piece you're reading without hauling the red pen out. Okay! That's the end of this incredibly disjointed and bumpy post. Next time, hopefully, I'll talk about the decolonization panel, which needed to be much longer than fifty minutes and could just be a course in itself. |

AuthorMia is a musician, teacher, writer, editor, and occasional photographer whose formal education is in music, psychology, and pedagogy. She enjoys reading a lot, thinking while on long drives, finding songs for each moment, and snoozing with her cat. Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed